Allocator’s Notebook: Union Square Ventures Funds I-III, 2004-2015

It's never too late to build one of the best funds in history

Nowadays, the investment community has more voices than ever. Some of these platforms are exceptional. Yet, while studying investors, I feel the need to go back in time, find some dusty articles or interviews, and hear investors directly as their younger selves who made the investment decisions at the time.

Why? Because USV in 2025 isn’t the same firm as USV in 2004, and Fred Wilson in 2025 isn’t the same person as Fred Wilson in 2004. Hence, we value having a singular focus on the interviews and resources of primary decision-makers from the time periods when they made their best decisions, and ignore all else. People change, memories disappear, hindsight misleads, and the worst is when we try to put a narrative on top, select for what sells and not for what’s true.

So, as we try to improve at recognizing the early innings of outlier investors, the aim is to isolate and study the past outliers with 10x, 20x, sometimes with 30x funds, ignoring everything else. While doing this, we will find the most boring and the lowest resolution videos possible, some out-of-print books, and share some of the takeaways from the eyes of an allocator.

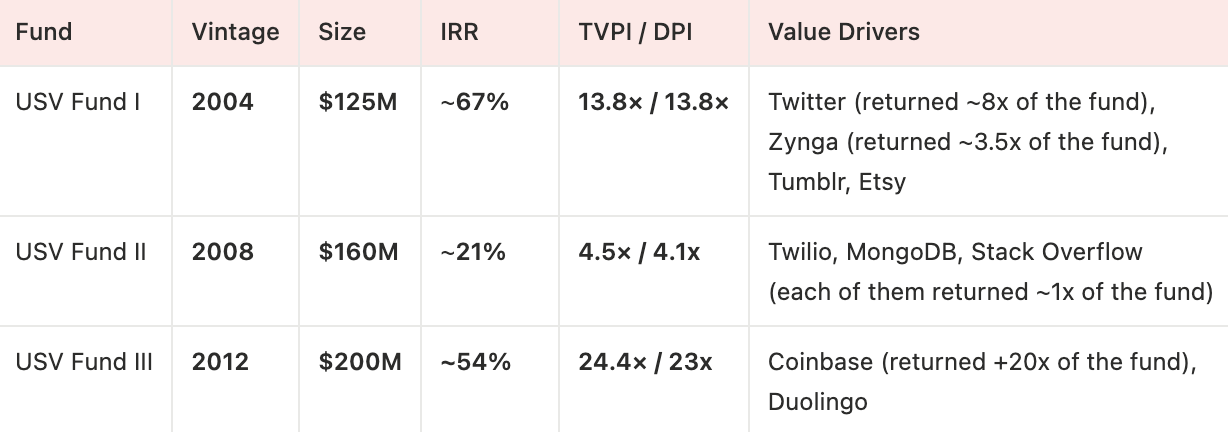

As part of the series, I will share data that is publicly available to give a general context to the performance of the funds and the key investments behind each, to set the stage. Data should be accurate enough, though I welcome any updates and corrections you have.

We now start with the first piece of the series that covers the initial few funds of USV. Feel free to move directly to the final ‘Learnings’ section if you’re familiar enough with the context.

Setting the Stage

Fred Wilson and Brad Burnham raised USV Fund I in 2004 as co-GPs. They have founded and operated USV in New York and didn’t have anyone on the ground in the Bay Area the entire time during Fund I-III. Fred has been a career investor since 1987, and USV is his third venture firm, second as a founder after Flatiron. Brad started his career as an operator and moved to venture with AT&T Ventures in 1993, and later co-founded TACODA in 2001, a USV Fund I company.

Albert Wagner first joined them as a venture partner in 2006 and became a GP in 2008 with USV Fund II after he exited Delicious, a USV Fund I company, to Yahoo. Before Fund III, the team expanded to five partners with the additions of John Buttrick in 2010, following his corporate law career, and Andy Weissman in 2011 after having founded Betaworks in 2007.

From the get-go, their LP base has been institutional. Fund I LPs included Los Angeles City Employees’ Retirement System (LACERS), Massachusetts Pension Reserves Investment Trust (MassPRIM), Oregon Investment Council / Oregon Public Employees Retirement System (OIC / Oregon PERS), and UTIMCO.

Key Companies

Twitter: USV Fund I led the $5M Series A round (2007).

Evan Williams (35*) had co-founded Blogger, and Jack Dorsey (31*) was a software engineer prior to Twitter. They were building Twitter inside Obvious Corp after Evan had approached Jack.

The investment resulted in an IPO in Nov 2013, at $14.2B, traded at ~$24B market cap later that day. USV reportedly held 6%, implying a stake worth ~$1B, ~8x of $125M Fund I.

Micro‑blogging was nascent at the time, and many investors doubted its importance and questioned monetization. Fred notes that, as a blogger himself, he immediately saw Twitter’s promise as a blog everyone can join.

Still, USV had to fight against Tier 1 competition. Fred and Brad flew to SF and closed the investment in a few days. They met Jake and Evan, who liked USV’s approach better as it was overlapping with theirs around just building the product and not thinking about the business model yet, whereas other investors pushed them to make deals with carriers.

*Age at the time of the USV investment

Zynga: USV Fund I led the $10M Series A round (2008).

Mark Pincus (42*) had been a serial entrepreneur whom Fred backed in his prior three companies, made some angel money, and his last company generated a mid-sized exit for Fred’s previous fund.

Zynga went public in 2011 at $9B and was later acquired by Take‑Two in 2022 ($12.7B). USV reportedly owned ~5% at IPO, implying a stake of ~$450M that was around ~3.5x of $125M Fund I.

The round was hot as Facebook games were booming, 2x the price of a normal Series A, and Fred says many investors passed because of the valuation and Mark not having gaming experience.

USV thought that mobile gaming was more like social, Mark had the right experience in social, and Mark had learned it, although his prior company wasn’t a big success.

*Age at the time of the USV investment

Coinbase: USV Fund III led the $5M Series A round (2013).

Armstrong (30*) was an Airbnb engineer and Ehrsam (25*) was a Goldman trader.

They went public in Apr 2021, at $85B. USV reportedly held around 7% which was worth ~$6B, 30x of $200M Fund III.

USV met Brian Armstrong via the YC network, and Initialized had led the $600k seed round prior. The company was likely to be seen by most Bay Area investors, though most of them dismissed crypto at the time.

*Age at the time of the USV investment

Learnings

It is never too late to build one of the best funds in history. When they raised and deployed USV Fund I, Fred was in his early 40s, having spent almost two decades in venture, and Brad was in his late 40s.

Fred had a clear chip on his shoulder. He lost his first venture firm, Flatiron, following a poor vintage during the dotcom boom, and went through a period of self-reflection before starting USV. He notes that the first thing on his mind was to prove wrong all the people who didn’t want to keep going with them.

Looking at their track record, it was not an obvious call that they would do well for LPs who colored between the lines. Fred had a good vintage (1996, Flatiron Fund I, ~5x on a $150M fund) followed by a bad one (1999, Flatiron Fund II, $350M) that resulted in the fund being shut down in 2001.

It was not an easy fundraise. They started with a 20-30 page whitepaper, outlining their investment theses and core investment principles, which didn’t resonate with LPs, and they didn’t have any commitments 6 months into their fundraise. They hired someone specialized in helping first funds to raise capital to help them get the main message across in 6-7 slides. It worked.

Unlike many outlier Fund Is, USV Fund I was visible to institutional capital. They had multiple US pensions and endowments as sizeable LPs.

USV Fund I of $125M was sizeable in 2004’s standards. $125M in 2004 was roughly in line with the industry average for 2004, and today’s equivalent would probably be $200-250M in size. Fred notes that they felt that a certain size was needed to allow them to go deep in their companies, one that sits between microfund and megafund.

Historicism doesn’t work as their story was not one where an emerging GP does well and emerges over time towards stabilizing returns. It was a rather wild ride with ups and downs. Fred’s story started well with Flatiron, suffered deeply during the dotcom, and then started smaller from scratch to become one of the best funds in the history of venture.

It’s not just about having special people in the room; context matters. Fred is open and reflective on his experience with Flatiron, between 1994-2000, having done well, but then scaling the firm from 4 to 25 people very fast, spending more time managing rather than investing, getting carried away in a crazy market, and eventually making bad investments at the wrong prices. When he restarted with USV, he set his initial conditions deliberately, having learned valuable lessons.

It was a small team deliberately kept that way and scaled organically. Following the experience with Flatiron, Fred was very deliberate in scaling the team slowly and preferred integrating the new GPs with patience and from the immediate ecosystem of people they know and trust.

It’s not about the physical proximity, but rather about the mind share. They built the fund in NYC (and without any GPs on the ground in the Bay Area) to become one of the best in history, with the biggest outliers still coming from the Bay Area. They had some great success from the NYC startup ecosystem, but the biggest value drivers like Coinbase, Twitter, and Zynga all came from the Bay Area. Sometimes one differentiates with a killer blog and by being an outsider vs. being the Nth local firm (our Brazilian friends call this the Gringo effect).

If done well, writing goes a long way. One of the biggest differences in Fred’s 2004 practices vs. pre-dotcom is blogging. Fred says thinking in public made them smarter and made it easier to meet people. Listening to their past videos, one sees that they were wrong in their theses at least as much as they were right, but had the creativity to recognize asymmetric ‘big if true’ ideas.

The initial fund thesis was a clear thematic bet in an unpopular category at the right time. Share of internet companies in total venture funding reached 50% by 2000, but around 2004, it was down to around 15% with life sciences and cleantech surging instead. Most LPs closed the door on them, having burnt their fingers in dotcom, but it was actually the dark before dawn.

Their first ideas were not their best ideas. The thesis started wider initially (companies like Tacoda, Instant Information) and then became more and more niche towards the application layer for the internet and large online networks of engaged users, where they nailed their biggest value drivers of USV Fund I, like Etsy, Twitter, Zynga.

You can look at the same thing, but see it differently. For their biggest value drivers, USV was neither first nor the only investor to see these companies. It seems like they have recognized the upside in ideas that might’ve been a bit out there at the time for the other investors.

A small team moving fast can win from Tier 1. For Twitter, they competed and won against top competition from Tier 1 Bay Area firms. He says that Jake and Evan asked them questions around the path to monetization and potential distribution deals with mobile handset manufacturers, and liked the USV answer of no distribution deals, just scale product and let the world come to you. Fred and Brad showed up and shook the hands of like-minded founders, and it worked.

Time is the real judge, and it is not over until it’s over. Listening to clips from the early 2000s, one cannot help but notice how some of the coolest companies go to zero in a few years or struggling ones become the real winners. See Fred’s chat with Chris Dixon below, in which they go over a number of companies as the hot, promising, successful ones of the day, like Bump or Color Labs, both raised the biggest seed rounds of 2011 and failed in a few years, and chat about Groupon, which was doing very well at the time. See the TWiST episode from 2015 where they talk about Kickstarter as a winner and the struggles of Zynga at the time. Time proved them wrong.

Exits took care of themselves. One of the USV’s core beliefs was that if one builds a valuable product, value accrual will take care of itself. See Fred’s post in 2007 after the Twitter investment, noting “The question everyone asks is ‘What is the business model?’ To be completely and totally honest, we don’t yet know.”. Funny enough, in his 2010 Mixergy interview, he predicts Elon’s eventual buyout, noting that “There is no reason why Twitter doesn’t have a change of ownership the way Skype did, and it doesn’t need to be an eBay type acquisition, more options we’ll see, not just sale to a strategic buyer or an IPO.”

Resources

If you want to get to the source of truth itself or just want to have some fun, here are some of the resources I have used while getting this piece together. Enjoy.

USV & AVC early blog posts

This is fascinating, thanks Yavuzhan!

Great breakdown Yavuzhan!